By Kathy Gannon

In Afghanistan, opium has bankrolled the good, the bad and the ugly. It has often been difficult to tell them apart.

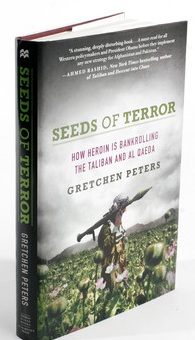

Seeds of Terror by Gretchen Peters

First there was the “good”: In the 1980s, opium-using and opium-funded holy warriors, backed by the U.S., fought invading Russians in the last Cold War battle. Even the CIA was said to be involved in the drug trade then, using poppies (from which opium is made) to finance the insurgency and, it was rumored, to get Russian soldiers hooked on drugs.

Then came the “bad”: In 1992, the holy warriors came to power when the Russians left Afghanistan. They grew poppies at a phenomenal rate and used the profits to underwrite their internecine killing, support terrorist training camps and fatten their overseas bank accounts. In 1996, they were thrown out by the “ugly”—the Taliban. In the end, the Taliban’s core membership was made up of some of the same holy warriors. Yet when the Taliban was ousted, it had wiped out opium production—perhaps to drive prices up and make a windfall, perhaps to win United Nations approval.

Today, the good, the bad and the ugly all flourish in Afghanistan—sometimes together, sometimes apart. But it’s not clear who is benefiting most from the drug trade. Is it the Taliban and al Qaeda or members of Afghanistan’s U.S.-backed government? Statistics vary wildly, but the U.N. estimates that drugs bring in upward of $300 million annually to the Taliban’s coffers. That still leaves billions unaccounted for.

In “Seeds of Terror,” Gretchen Peters makes a valiant attempt to dissect this difficult subject, but even her exhaustive research leaves a lot questions unanswered. She cites documents from U.S. intelligence sources and the Drug Enforcement Agency that portray the U.S. and its allies as reluctant partners with bad guys, who routinely exploit their country’s poppy crops for various purposes. Alliances with the unsavory, the reasoning goes, can be used to fight for a greater good—beating the Soviets in the 1980s, beating back the resurgent Taliban now.

But such a claim obscures the uncomfortable truth that the U.S. and the international community have had a direct role in putting the unsavory in power. In “Seeds of Terror,” the claim appears to be corroborated—but by false information. “The Northern Alliance swept into Kabul installing its people . . . in key security posts,” Ms. Peters writes, referring to late 2001. “To cobble together support for his weak coalition government, the U.S. appointed leader Hamid Karzai, who began handing out important positions like they were trophies.”

But the Northern Alliance didn’t sweep into Kabul. It was put there by the U.S.-led Operation Enduring Freedom. And it wasn’t Mr. Karzai who handed out the trophies but the U.N., with the backing of Washington, at a meeting in Bonn, Germany, in December 2001. The Bonn agreement decided who would occupy the new government’s key posts, including key security posts and the presidency itself (which went to Mr. Karzai). Thus many in Afghanistan today say that the West is culpable for Afghanistan’s bad governance—and for its increasing poppy production—because the U.S. and its allies returned to power the very warlords and drug kingpins who had given rise to the Taliban in the first place.

A great deal of misinformation has emerged since the collapse of the Taliban in 2001, and it is repeated so often that it is now taken for truth. An example from “Seeds of Terror”: that the Taliban’s one-eyed leader, Mullah Mohammed Omar, was linked to Osama bin Laden before the Taliban took over Kabul in September 1996. To make that connection, Ms. Peters says that Omar belonged to a mujahedeen group—the Hezb-e-Islami, under the leadership of the Yunus Khalis—that sheltered bin Laden when he fled Sudan for eastern Afghanistan in early 1996. But Omar belonged to Mohammed Nabi Mohammedi’s Harakat-eIslami group, which had no affiliation to bin Laden. During the Russian occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s, Omar fought in southern Kandahar and didn’t know bin Laden before the Taliban takeover.

At first blush this would seem to be a minor error. Yet it is hugely significant, because the men who actually welcomed bin Laden when he reached Afghanistan from Sudan were the same men that the U.S. and its allies in Enduring Freedom put into power once the Taliban had been driven out. These same new rulers have led the long hunt for bin Laden. No surprise that he hasn’t been found.

The installation of the unsavory into power might also explain how Afghanistan went from being essentially opium-free in 2001 to producing more than 4,000 tons of opium during just the first two post-Taliban years. Those in power, supported by the U.S. and its allies, then did exactly what they had done before the Taliban took over. They set up little fiefdoms and extorted money from the international community to stop producing drugs. Yet all the while they were also planting poppies in previously poppy-free areas. Some in the Afghan military and anti-narcotics ministry have drug-dealing reputations that go back decades.

It is Ms. Peters’s belief that, ultimately, opium is at the heart of al Qaeda’s and the Taliban’s financing and that following the drug-money trail and choking it off is central to winning the war on terror. But the answer to the big question is more important: Who has the deepest involvement in the drug trade—the Taliban or the Western-allied government? Is the lawlessness that has made winning the peace in Afghanistan so elusive rooted in the government’s participation in the drug trade? At some point, the U.S. and its allies will have to clean out relationships that have been built on nefarious ties between Kabul’s government and its patrons. Such an effort is a key to Afghanistan’s future and to the value of Afghanistan’s elections this summer.

—Ms. Gannon, the author of “I Is for Infidel,” has been the Associated Press correspondent in Pakistan and Afghanistan for the past 20 years.