McClatchy

American soldiers herded the detainees into holding pens of razor-sharp wire, the kind that's used to corral livestock.

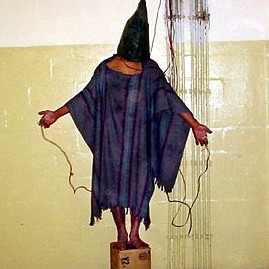

The guards kicked, kneed and punched many of the men until they collapsed in pain. US troops shackled and dragged other detainees to small isolation rooms, then hung them by their wrists from chains dangling from the wire mesh ceiling.

The human rights scandal now known as "Abu Ghraib" in Iraq

Former guards and detainees whom McClatchy interviewed said Bagram was a centre of systematic brutality for at least 20 months, starting in late 2001. Yet the soldiers responsible have escaped serious punishment.

The public outcry in the United States and abroad has focused on detainee abuse at the US naval base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, but sadistic violence first appeared at Bagram, north of Kabul, and at a similar US internment camp at Kandahar airfield in southern Afghanistan.

The eight-month McClatchy investigation found a pattern of abuse that continued for years. The abuse of detainees at Bagram has been reported by US media organisations, in particular the New York Times, which broke several developments in the story.

But the extent of the mistreatment, and that it eclipsed the alleged abuse at Guantánamo, hasn't previously been revealed.

Guards said they routinely beat their prisoners to retaliate for al-Qaida's 9/11 attacks, unaware that the vast majority of the detainees had little or no connection to al-Qaida.

Former detainees at Bagram and Kandahar said they were beaten regularly. Of the 41 former Bagram detainees whom McClatchy interviewed, 28 said that guards or interrogators had assaulted them. Only eight of those men said they were beaten at Guantánamo Bay.

Because President Bush loosened or eliminated the rules governing the treatment of so-called enemy combatants, however, few US troops have been disciplined under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, and no serious punishments have been administered, even in the cases of two detainees who died after American guards beat them.

In an effort to assemble as complete a picture as possible of US detention practices, McClatchy reporters interviewed 66 former detainees, double-checked key elements of their accounts, spoke with US soldiers who'd served as detention camp guards and reviewed thousands of pages of records from US army courts-martial and human rights reports.

The Bush administration refuses to release full records of detainee treatment in the war on terrorism, and no senior Bush administration official would agree to an on-the-record interview to discuss McClatchy's findings.

The brutality at Bagram peaked in December 2002, when US soldiers beat two Afghan detainees, Habibullah and Dilawar, to death as they hung by their wrists. Habibullah and Dilawar, like many Afghans, have only one name.

Dilawar died on December 10, seven days after Habibullah died.

He'd been hit in his leg so many times that the tissue was "falling apart" and had "basically been pulpified," said then-Lieutenant Colonel Elizabeth Rouse, the US air force medical examiner who performed the autopsy on him.

The only American officer who's been reprimanded for the deaths of Habibullah and Dilawar is Army Captain Christopher Beiring, who commanded the 377th military police company, a US army reserve unit from Cincinnati, Ohio, from the summer of 2002 to the spring of 2003.

The soldier who faced the most serious charges, Specialist Willie Brand, admitted that he hit Dilawar about 37 times, including 30 times in the flesh around the knees during one session in an isolation cell.

Brand, who faced up to 11 years in prison, was reduced in rank to private - his only punishment - after he was found guilty of assaulting and maiming Dilawar.

Former detainees interviewed by McClatchy and by some human rights groups, however, claimed that the violence was rampant from late 2001 until the summer of 2003 or later, at least 20 months.

Although they were at Bagram at different times and speak different languages, the 28 former detainees who told McClatchy that they'd been abused there told strikingly similar stories:

Soldiers who served at Bagram starting in the summer of 2002 confirmed that detainees there were struck routinely.

"Whether they got in trouble or not, everybody struck a detainee at some point," said Brian Cammack, a former specialist with the 377th military police company. He was sentenced to three months in military confinement and a dishonourable discharge for hitting Habibullah.

Specialist Jeremy Callaway, who admitted to striking about 12 detainees at Bagram, told military investigators in sworn testimony that he was uncomfortable following orders to "mentally and physically break the detainees." He didn't go into detail.

"I guess you can call it torture," said Callaway, who served in the 377th from August 2002 to January 2003.

Asked why someone would abuse a detainee, Callaway told military investigators: "Retribution for September 11 2001."

Almost none of the detainees at Bagram, however, had anything to do with the terrorist attacks.

Major Jeff Bovarnick, the former chief legal officer for operational law in Afghanistan and Bagram legal adviser, said in a sworn statement that of 500 detainees he knew of who'd passed through Bagram, only about 10 were high-value targets, the military's term for senior terrorist operatives.

The mistreatment of detainees at Bagram, some legal experts said, may have been a violation of the 1949 Geneva Convention on prisoners of war, which forbids violence against or humiliating treatment of detainees.

The US War Crimes Act of 1996 imposes penalties up to death for such mistreatment.

At Bagram, however, the rules didn't apply. In February 2002, President Bush issued an order denying suspected Taliban and al-Qaida detainees prisoner-of-war status.

He also denied them basic Geneva protections known as Common Article Three, which sets a minimum standard for humane treatment.

In 2006, Bush pushed Congress to narrow the definition of a war crime under the War Crimes Act, making prosecution even more difficult.

The military police at Bagram had guidelines, Army Regulation 190-47, telling them they couldn't chain prisoners to doors or to the ceiling. They also had Army Regulation 190-8, which said that humiliating detainees wasn't allowed.

Neither was applicable at Bagram, however, said Bovarnick, the former senior legal officer for the installation.

The military police rulebook saying that enemy prisoners of war should be treated humanely didn't apply, he said, because the detainees weren't prisoners of war, according to the Bush administration's decision to withhold Geneva Convention protections from suspected Taliban and al-Qaida detainees.

The military police guide for the army correctional system, which prohibits "securing a prisoner to a fixed object, except in emergencies," wasn't applicable, either, because Bagram wasn't a correctional facility, Bovarnick told investigators in 2004.

"I do not believe there is a document anywhere which states that ... either regulation applies, and there is clear guidance by the secretary of defence that detainees were not EPWs," or enemy prisoners of war, Bovarnick said.

Compounding the problem, military police guards and interrogators lacked proper training and received little instruction from commanders about how to do their jobs, according to sworn testimony taken during military investigations and interviews by McClatchy.

Senior Pentagon officials refused to be interviewed for this article.

In response to a series of questions and interview requests, Colonel Gary Keck, a US defence department spokesman, released this statement: "The Department of Defence policy is clear - we treat all detainees humanely. The United States operates safe, humane and professional detention operations for unlawful enemy combatants at war with this country."

No US military officer above the rank of captain has been called to account for what happened at Bagram.