Jochen-Martin Gutsch

A young Afghan has been sentenced to death for printing out a Web page in which Muhammad is described as a misogynistic prophet. The case will help to determine whether an Islamic country can open itself up to the West.

Sayed Pervez Kambaksh can walk four or five steps forward and backward and three to the side. Aside from the metal bunk bed, a table, a chair and a wooden shelf, his cell contains a primitive toilet and a shower that doesn't seem to work. In Afghanistan, this counts as a good cell. After all, it is a cell for a very special prisoner.

One of the most disconcerting aspects of being a prisoner here is that there is nothing to do. When the door locks behind him, he is left with a sense of uncertainty and with his thoughts, which usually revolve around death and salvation, right and wrong, thoughts he constantly chews over in his mind like a tough piece of meat.

He has received two visits from his brother Yaqub and one from his father. After that, Kambaksh was left to wait for something to happen, hoping that the appeals court in Kabul, which is reviewing his appeal, will do something, and that the judges will understand that they cannot simply string him up or have him face a firing squad for a simple piece of paper.

The Pol-i-Charkhi prison seems to appear out of nowhere like a stone spaceship. Located on the eastern edge of the Afghan capital Kabul, the prison is reached by driving to the end of an unpaved road, a road with potholes so deep that they can engulf a car tire. Depending on the weather and season, the road is either hard and dusty or consists of a deep, brown mud. It leads through a barren landscape devoid of trees and people, ending in front of a tall, steel gate flanked by two stone watchtowers.

The prison itself consists of a collection of faded buildings, narrow and rectangular like upended shoeboxes, constructed in the 1970s and used by the Soviets, the Taliban and now the country's new government. The prison holds 3,200 prisoners: murderers, terrorists, kidnappers, thieves and a handful of poor souls who have no money and no legal representation -- and of whom no one can really say whether they are guilty or innocent.

Sayed Pervez Kambaksh happened upon the text that was to be his undoing on an Iranian Web site. The author called himself Arash. It was neither an academic text nor a serious discussion, but more of an aimless rant. There are hundreds of similar sites on the Internet. The text listed verses in the Koran, followed by interpretations intended to prove that Islam is a misogynistic religion. It isn't difficult to guess which lines eventually led to the charges being filed against Kambaksh.

The text read:

Muhammad sinned often. Muhammad subjugated women. The Koran portrays women as if they were not quite sane. Islam is a religion that is against women.

The Koran justifies Muhammad's sins. Whenever Muhammad wanted something, he would sing a sura and claim that it was coming directly from Allah. He simply banned everything that didn't suit him and allowed the things he liked. It's a joke. This is the true face of Islam, Allah and Muhammad.

Kambaksh may have overestimated his own country. Or perhaps he was deliberately pushing his luck, and maybe he was simply trying to determine how far one could go in the new Afghanistan.

Rising Tension

Kambaksh copied a few passages from the text and arranged them. Whether he wrote a few lines of his own is unclear. Then he printed the text, and later handed out a few copies to fellow students at the university he attended in the city of Mazar-i-Sharif. He wanted to stimulate discussion, just as he had once discussed Marx and Hegel.

The matter quickly gained momentum. A copy of his printout reached the National Directorate of Security (NDS), Afghanistan's domestic intelligence agency, which has its offices across the street from the university. Kambaksh was questioned and then released. His opponents soon began to gather together at the university. Students and instructors organized protests against Kambaksh, accusing him of blasphemy. The mood became increasingly tense, as more and more copies of the text turned up.

KBAUL, Jan 31: Members of Afghanistan Solidarity Party conduct a protecting demo, considering the death sentence illegal which is handed down by a court to a young journalist Sayed Parviz Kambakhsh accused of blasphemy. PAJHWOK/Ahmadullah Salemi

To this day, Kambaksh insists that he doesn't know who made the extra copies and where they came from. Soon the copies numbered in the hundreds, and his name was at the top of every one of them. The situation became uncomfortable for Kambaksh. Mullahs at the city's Blue Mosque demanded action be taken. Kambaksh began spending his nights at the houses of friends, and he stopped going to the university. A man from the NDS called his older brother, Yaqub, to tell him that Kambaksh should turn himself in to the agency -- for his own safety. The population, the man said, was agitated, and Kambaksh would be protected against attacks if he was in NDS custody.

Yaqub drove his brother to the gate of the NDS complex, convinced that he was doing the right thing. It was Oct. 27, and it would be Kambaksh's last day as a free man. "I was there for one week," he recalls. "They interrogated me several times a day. At some point, I was at my wits' end and I asked them: 'What do you want from me?' They shoved a piece of paper in front of me on which it was stated that I had copied the text from the Internet, added a few of my own lines, and then duplicated and distributed it. I signed the piece of paper." It was a confession.

An Intimate Court

On Jan. 22, Kambaksh, now a prisoner, was taken to the hearing room at the provincial court in Mazar-i-Sharif. The city is in northern Afghanistan, in a region where German troops are stationed. The hearing room was small and intimate, with its vase of plastic flowers, curtains and a framed photograph of President Hamid Karzai. The room seemed to say: Don't worry, it won't be as bad as you think.

For the presiding judge, Shamsurahman Mohmand, who was wearing heavy, gold-framed sunglasses to protect his sensitive eyes, the room serves as both his office and courtroom. Two other judges sat next to him. The charges were read by Shafiqa Akbar, an experienced prosecutor and a friendly-seeming woman, who was filling in for a sick colleague on that day. It was approximately 4 p.m. Although it was a public hearing, no spectators had found their way to the small room. Kambaksh had no attorney. He was defending himself.

The case revolved around a single sheet of paper, a copy of the text, which Judge Mohmand removed from the file and held up for everyone to see. The sheet of people was the entire case.

Mazar-i-Sharif is smaller and more provincial than Kabul. But the air is better and the city is home to Afghanistan's most beautiful house of worship, the Blue Mosque. Kambaksh was a fourth-year journalism student at the city's university. He shared a small apartment with his older brother Yaqub, a journalist.

Kambaksh was not a bad student, but he periodically felt limited by his environment. The lectures bored him and he considered the instructors to be dogmatic. They were not helping him grow intellectually. After reading books about politics and philosophy, Marx and Hegel at home, he wanted to talk about their view of the world.

Kambaksh comes from a family that is relatively non-religious, at least by Afghan standards. The father was an instructor at the military academy in Kabul and had attended university in Moscow. When the communist government fell in 1991, Kambaksh's father quit his job and took his family to the north, where he found work in an exchange office. Then he opened a bookstore.

Kambaksh and his brother Yaqub were given books to read by some of the world's preeminent writers, including Goethe, Russian classics by Gorky, Dostoyevsky and Chekhov. Later they read Nietzsche, Sartre and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. For someone with Kambaksh's upbringing, a country like Afghanistan is bound to become very confining before long.

'It Wasn't Easy for Me to Demand the Death Penalty'

"He is easily offended," says Nazir, a fellow student. "He isn't an easy person. Pervez asked questions about politics and religions, questions the instructors didn't want to or couldn't answer. Sometimes they would accuse him of thinking in an un-Islamic way, and then he would accuse them of not thinking at all."

There were complaints. The court file contains an instructor's official complaint against Kambaksh for being disruptive in class. "Pervez underestimated the whole thing until the end," says Nazir, his fellow student.

On Jan. 22, the day of the hearing, Kambaksh based his case on a single argument, more or less: his right to freedom of opinion, holding it out to the court like a protective shield. He had written down a statement, which he was not permitted to read in its entirety. He invoked an article in the constitution. The court invoked Sharia law. He spoke of laws written by humans, and they spoke of laws created by God. Kambaksh and the court faced off like two boxers on the opposite sides of the ring.

"He kept repeating that he had not committed a crime, and that he believes in freedom of opinion," recalls Shafiqa Akbar, who has been working in the judicial service for 26 years and has been a prosecutor for 23 years. "He began to read a statement, but it was not a legal plea. He wanted to give a political speech. He wanted to have a discussion with us. I said: 'My boy, are you aware that this is a courtroom?'"

At the appeals court in Kabul, Akbar has the reputation of being one of the best prosecutors in the provinces. "It wasn't easy for me to demand the death penalty," she says. "He was still so young."

Judge Shamsurahman Mohmand, 53, a graduate of the Department of Sharia Law at the University of Kabul, presided over the hearing. "I asked him whether he could defend himself. He said: 'Yes.' I asked him about his health. He said: 'Everything is fine.' Then we began."

It was no layman's court, devoid of legal expertise, that convened on that day in Mazar-i-Sharif. Nor was it a tribunal of religious fanatics. This is what makes the case so difficult. It would be easy to explain away the verdict if it had come from laymen or fanatics. But not with this court. "Under Article 130 of the constitution, Sharia law can be applied to crimes that are not covered by the criminal code. And so I requested that Sharia be applied," says Akbar.

"The evidence against Kambaksh was clear," Akbar says. "We had a sheet of paper containing the text, with his name at the top. We had his confession. We had 11 written statements from students and instructors at the university. He was told that he could request an attorney. But he didn't. He was told that he had the right to remain silent. But he didn't. He was told that he should name counter witnesses. But he didn't. We said: 'Appoint your father, someone we can talk to, because you don't understand us.' But he continued to refuse."

Shafiqa Akbar shrugs her shoulders. Her image of Kambaksh is that of an obstinate child. He was given the hand that would have saved him, but he rebuffed it. Bridges were built for him, but he refused to walk across them. Judge Mohmand says: "I stood up and walked over to him. I said: 'My son, you can deny everything. Just say that you were not the source of this piece of paper. You have the right to remain silent. You are making a mistake.'"

Kambaksh says that his brother Yaqub tried to get him an attorney, but that no one felt confident enough to defend someone accused of blasphemy. Kambaksh says that he was under the impression that the sentence had already been decided, and that everything went very quickly. Kambaksh says that the things he was accused of are not liable to prosecution. He insists that freedom of opinion is unassailable.

Both sides were unwavering, firmly entrenched in their respective worlds.

Judge Mohmand handed down the death penalty. A copy of the sentence -- another piece of paper -- was handed to Kambaksh, who was then led from the courtroom.

A Barometer of Progress

Visiting Kambaksh at the Pol-i-Charkhi Prison is no easy matter. It requires a permit from Sarwar Danish, the country's justice minister. The Kambaksh case has become famous, mostly because no one in Europe or the United States understands why the case should exist in the first place. However one feels about blasphemy, it should not be punishable by death, goes the thinking.

Thus, a case that began in a small provincial court in Afghanistan entered the realm of world politics. President Karzai became involved, as did the United Nations, US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, and Hans-Gert Pöttering, the president of the European Parliament. The British newspaper The Independent started a petition among its readers to gain the release of Kambaksh in faraway Afghanistan, and his cause even triggered a small demonstration in Kabul.

The case now functions as a barometer of progress in the country. The West sends soldiers, money and advisors to Afghanistan. Everyone is waiting for the country to make its big step forward, a step in the direction of democracy, human rights and all the other good things from places like the United States and Germany, things of which no one can say for sure whether the Afghans even want them. Kambaksh's story now appears as evidence that not much has changed in Afghanistan.

Sarwar Danish, a quiet, amiable man, has served as Afghanistan's justice minister for more than three years. In the late 1970s, he fled from the Soviets to Iran, and after the fall of the Taliban he returned to Afghanistan. Now he sits in his office, his back to a bookshelf full of the kinds of law books lawyers like to consult, and gazes at a gilded statue of Justice judiciously dispensing the law on the desk in front of him.

Danish could call it a mistake. He could say that the provincial court up in the north issued a flawed ruling. But he doesn't.

"This person, Kambaksh, is a young student, a radical who doesn't consider his actions," he says. "He published things that are directed against our religion. The Koran is revered and respected by all Muslims. This is why Muslims cannot be expected to accept unjustified, hostile attacks. The attacks must be treated and punished as blasphemy. Blasphemy is prohibited everywhere in the world, and certainly in Germany. A court of appeal will soon review the sentence against Kambaksh. In Afghanistan, there are many steps before an execution can take place. In the end, the president makes the final decision."

Danish taps his finger against the gilded statue of Justice on his desk. "The symbol of law and justice," he says. "An international symbol." He makes it sound like a shared direction, like some straightforward, global idea. But sitting in Danish's office, one gains a sense of how complicated, in fact, everything is.

And how will President Karzai decide, if it becomes his decision to make? Danish smiles politely. "Our president has only allowed 15 people to be executed in six years. He doesn't like to do it at all."

Danish pulls a small, blue book from his bookshelf, which he intends to give as a present at the end of the conversation. He glances at the attractive cover with its gold lettering. The book is a copy of the Afghan constitution. But whether it means much to Danish is questionable.

Article 34 of this constitution states that freedom of opinion is inviolable. But Article 1 defines Afghanistan as an Islamic republic, and Article 3 stipulates that no law may contradict the holy religion of Islam. Afghans can think, say and write what they please. But they start running into problems when God enters the picture.

'They Sentenced Pervez in Order to Silence Me'

It is mostly because of Yaqub, the brother, that the case did not remain in the provincial court, and that it instead came to the attention of President Karzai and Condoleezza Rice. Yaqub wrote about his brother's predicament. He gave interviews, contacted Western aid organizations and flew to Europe, where he had been invited to talk about the case. In Amsterdam, he bought a pair of red socks that have since become one of his favorite pairs. The socks feature a likeness of Che Guevara in black and the word "Revolución" in yellow.

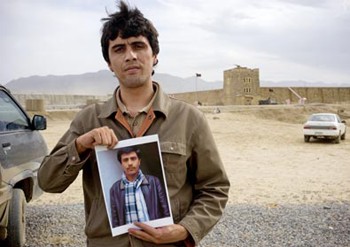

Yaqub Ibrahimi, Kambakhsh's brother: "They sentenced Pervez in order to silence me." (Photo: Thomas Grabka)

Yaqub is doing what he believes is his duty, as the older brother. He feels guilty about what happened to his brother. Yaqub refuses to be picked up anywhere. He says, on the telephone, that he will meet me at a certain location. Now he stares through the window of a small café, looking at Kabul in the valley below. It is night and the city becomes quieter and quieter, like a machine that has been switched off.

Yaqub Ibrahimi has been living in Kabul for several weeks. He sleeps in various places, in the apartments of friends and acquaintances, changing locations for security reason, he says.

"The whole thing is probably about me," says Yaqub. "They sentenced Pervez in order to silence me."

Who are "they?"

"The people I have written about. They've been waiting for an opportunity." He glances nervously around the café, looking as if he were about to jump up from his seat. "The piece of paper Pervez printed out was that opportunity."

Yaqub works for the Institute for War & Peace Reporting, a London-based organization that trains journalists in crisis regions. He reports on corruption and human rights violations, and he has written stories describing the lost country that Afghanistan seems to have been for a long time. He wrote about a military commander, a former mujahedeen and powerful man in his district, who kidnapped underage boys, dressed them as girls, ordered them to dance for him and then raped them. He also wrote about another commander who took away a mother's daughter and traded her for a fighting dog.

For that story, Yaqub received Italy's "Journalist of the Year" award in March. He became famous. But in Afghanistan he paid a heavy price for his fame.

"I had been getting threatening phone calls for some time. They told me to watch out, that they would find ways to get rid of me. At one point, five men with Kalashnikovs were standing in front of my apartment. Luckily I wasn't home that evening. The landlord told me about it the next day."

Perhaps everything is related: Yaqub's story about the commander and the death sentence against his brother, Pervez Kambaksh. Perhaps it is a plot. The problem is not whether or not this is true, but that he even considers such a conspiracy to be possible. Yaqub is only 27, and his brother is 23. They are the new generation, the kinds of people Afghanistan sorely needs if the country is to be rebuilt, but they have already lost confidence in the country's new age and new rulers. They do not believe that there is a new Afghanistan, but that, in fact, the country is still its old, rotten, threatening, lawless self. For people like Yaqub, the case boils down to a death sentence and five men with Kalashnikovs.

Yaqub says that Pervez will have to leave the country if he is acquitted. Everyone knows his name now, knows him as the man who committed blasphemy.

Has Yaqub actually read the text that his brother distributed?

"The text is not important," says Yaqub. "In Afghanistan, one has to be able to read and write everything. Freedom of opinion is at stake here."

Shafiqa Akbar, the prosecutor, wears a dark, patterned headscarf, and there is little severity in her face. Her office, a sparse, well-lit room, is only a few hundred meters from the small courtroom where Kambaksh was sentenced and where Judge Shamsurahman Mohmand has his office. Both Akbar and Mohmand have no doubt that they did the right thing.

"There was no other option but the death penalty," says Akbar.

"Someone who commits such a crime deserves to be put to death," says Judge Mohmand. There is no alternative. "Kambaksh insulted the religion of many millions of people, without taking national harmony into account," says Judge Mohmand.

"I hope you can understand that I cannot repeat the primitive insults to the Prophet and to Islam that the text contained," says Akbar. "But they were considerable."

And Article 34, the clause about freedom of opinion?

"Freedom of opinion is a very valuable thing. But that doesn't mean that one should be allowed to violate religious sentiments. Insulting a religion, any religion, is not part of freedom of opinion, but is a criminal offence," says Akbar.

But is it necessary to put someone to death for a violation of religious sentiments?

"There was no other possibility, unfortunately," says Judge Mohmand. "Under Sharia, this is the only option."

The death penalty for a text?

"I have already handed down several death sentences," says Mohmand. "What I do not understand is why this one is causing such a stir, especially abroad. There are no mistakes in the ruling."

Mohmand shakes his head. He laughs periodically during the conversation. He says that he has trouble understanding all the fuss, and why some journalists from halfway around the world have come to see him and are asking questions about law and a religion that they will never understand. In that, at least, he is right. The interview ends without answers. There is too much of a divide between the two cultures. It is an odd feeling.

'I Am a Muslim'

Sayed Pervez Kambaksh traveled along the unpaved road outside Kabul and passed through the gate at the Pol-i-Charkhi prison on March 27. He had a long journey behind him: more than 450 kilometers (280 miles) from the prison in Mazar-i-Sharif in the north to this place on the dusty outskirts of Kabul. He was brought to Pol-i-Charkhi in a car, his feet chained together and accompanied by two armed policemen.

After being admitted, his head was shaved and he was taken to a single-occupancy cell in a new wing built with Canadian money. That was when the door slammed shut behind Kambaksh, sentenced to death for blasphemy, false interpretation of the Koran and insulting the Prophet Muhammad and Islam.

There are books lying on his bed. Kambaksh says that he reads a lot -- fiction and poetry, mostly. He has the face of a boy. Shivering, he tightens his black leather jacket, which he wears over traditional clothing consisting of a thin, baggy fabric shirt and thin, baggy fabric trousers. He wears colorless rubber or plastic sandals on his otherwise bare feet. Kambaksh looks at the five prison guards standing in the cell, monitoring what he says. They look at him with the curiosity of people observing a rare animal.

Kambaksh was due to appear before an appeals court in Kabul Sunday. He hoped he might walk free, but in the end the hearing was adjourned.