The Washington Post, January 8, 2015

Heroin addiction spreads with alarming speed across Afghanistan

This culvert beside the desiccated Kabul River, a notorious gathering spot for drug addicts, is at the heart of a scourge that swelled after the U.S. invasion in 2001 and has spread across Afghanistan with alarming speed in recent years

By Pamela Constable

KABUL — The scene beneath a crumbling overpass in this capital city was a vision from hell. Hundreds of figures huddled together in the shadows, crouching amid garbage and fetid pools of water. Some injected heroin into each other’s limbs or groins in full view; others hid under filthy shawls to cook and inhale it.

An elderly man in a turban wandered among the addicts, showing them a snapshot of his missing son. A young man lay unconscious on a muddy blanket after a long, cold night, while others speculated whether he was already dead.

“I love my son, but he is sick from drugs,” said the old man, a laborer who gave his name as Ghausuddin. He looked at the photo and began to weep. “He must be cured. All of these boys must be cured or they must be killed. They are destroying Afghanistan. A whole generation is being destroyed.”

This culvert beside the desiccated Kabul River, a notorious gathering spot for drug addicts, is at the heart of a scourge that swelled after the U.S. invasion in 2001 and has spread across Afghanistan with alarming speed in recent years. The United Nations estimates that there are as many as 1.6 million drug users in Afghan cities — about 5.2 percent of the population — up from 940,000 in 2009. As many as 3 million more are believed to be in the countryside.

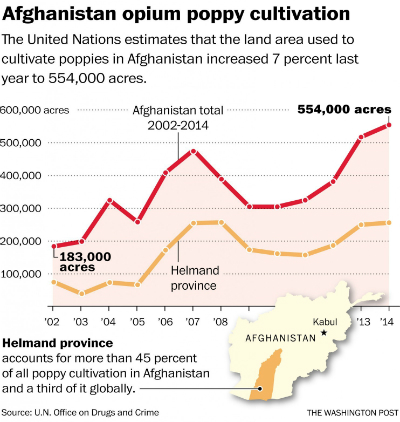

The principal causes of this epidemic, officials say, are rampant unemployment, the return of addicted workers from wartime exile in Iran or Pakistan, and bumper harvests of opium poppies. Despite years of costly international efforts to curb the traditional Afghan crop, led by the U.S. government, it is thriving more than ever. According to U.S. officials, a record 520,000 acres of land were used to grow poppies in 2013.

Booming illegal economy

Drug addicts gather under a bridge in Kabul, where they sleep through cold nights and inject and snort drugs by day. (Pam Constable/The Washington Post)

Afghan farmers have grown opium poppies for generations, but the vast majority of the drug was exported and relatively few Afghans consumed it. In 2000, the Taliban regime deemed poppy growing un-Islamic and banned the practice. By 2005, though, the Taliban had returned as a predatory militia, hampering eradication and crop substitution programs sponsored by the United States. Production roared back, and domestic heroin use grew with it.

“People used to assume that we cultivated poppy but only for export. Today . . . at least 5 percent of the drugs produced in Afghanistan are consumed here, and they are imported from the neighbors as well,” said Mohammed Ibrahim Azhar, the deputy minister of counternarcotics. “Our security forces are putting all their resources into fighting the insurgents, and the illegal economy is booming.”

The profits from opium and heroin are temptingly huge, and the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime reported that in 2014 Afghan poppy farmers took in about $850 million — more than twice as much as five years before. In addition, officials said, processing labs have sprung up in several border provinces, and street sales of refined powder have become a major business in Kabul and several provincial capitals.

But domestic law enforcement efforts have been limited and ineffective, with only about 2,000 police officers nationwide assigned to anti-narcotics work. Corruption is so entrenched that a major drug trafficker, whose rare 20-year sentence was hailed as a success for the ambitious U.S. drug enforcement support program, bribed his way out of an Afghan prison recently and vanished.Little help available

This week, several addicts in the culvert said they spent about $2 daily on small packets of heroin. Sellers constantly came and went. “Doctors” charged 20 cents to find veins that had not collapsed from overuse, then injected powder mixed with water on the spot.

A plainclothes officer was also there, talking with addicts and keeping an eye out for exchanges of cash and drugs. He said that he and his partner usually arrest two or three people a day, but that many were so addicted that they had to be taken to a hospital for detoxification after a night in jail.

“We work hard, but we are overwhelmed. The number of addicts is increasing by the day,” said the officer, who gave his name as Khalid. He gestured toward the mass of huddled figures. “Every day three or four of them die,” he said. “They come here, and they never leave.”

Although the number of addicts has soared, there is still very little help available for those who want to quit. Officials said there are 170 drug treatment facilities around the country, most built with foreign funds, but their total capacity is only 39,000 patients, and the few residential programs release addicts to the street after 40 days with little follow-up.

(Photo: THe Washington Post)

Azhar said that plans are underway to build new centers in Nangahar and Helmand provinces, but that 75 percent of the addicts who inject drugs are concentrated in Kabul. He also said preliminary results of a new survey suggest that the number of rural drug users is much higher than previously thought.

“We are no worse off than other countries in the region,” he said, citing high addiction rates in Pakistan and Iran. “At least here we admit the problem exists. We see it as a humanitarian issue, and we welcome anyone who wants to help.”

This week, a dozen addicts surrounded a visiting journalist next to the culvert and spilled out their stories. Some were bleary-eyed and semi-coherent; others were angry or crying. Their ages and backgrounds varied, but most had two things in common: They had returned to their homeland after years in Iran or Pakistan, and they had been jobless or surviving on menial labor for many months. All were men.

“I started to take powder when I was in Iran, because it gave me strength to work all day. But now powder does not give me relief, so I have to inject it instead,” said a father of four named Nasir, 39. He said he spent most of his petty earnings on drugs and was ashamed to go home. “There are hundreds of others like me here,” he said.

A gaunt young man with a grime-streaked face broke into the conversation, saying he was desperate to return to his home in Ghazni province. Tears ran down his face, and his hands shook. He said he was 19.

“I am stuck here, and I can’t go back,” he said. “My family doesn’t know I am living under a bridge. I am so ashamed and sad. I don’t know what to do.”

Khalid, the anti-narcotics officer, shook his head in frustration and disgust. The old man with the snapshot tugged at his sleeve, and the officer recognized the face on it.

“We arrested that guy last night for selling drugs,” he explained. “He is in a safe place now, and we will see what happens. Go home, old man, there is nothing you can do for him.”Pamela Constable covers issues related to immigration policy, immigrant communities and international figures and issues that crop up in our local and regional midst.

Characters Count: 8408