The New York Times, July 6, 2012

Billions Down the Afghan Hole

By Huguette Labelle

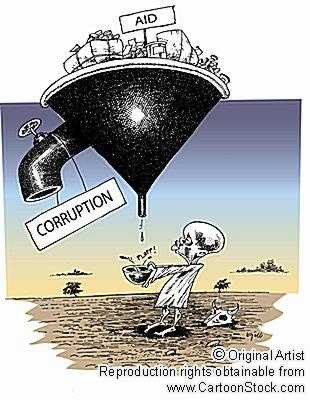

The major donors and Afghan government officials meeting in Tokyo on Sunday to discuss future aid to Afghanistan have to face up to a bitter truth: As much as $1 billion of the $8 billion donated in the past eight years has been lost to corruption. All governments in Tokyo must show that business as usual cannot continue. An agreement worth $4 billion is at stake.

Turning off the aid taps is not an option. This would hurt the poorest, increase instability and likely lead to illicit flows taking the place of donor funding. Donors and the Afghan government need an enforceable plan to tackle the issue. They don’t need more words.

Corruption in the country is nothing new, but it is worsening. Afghanistan has had a long history of conflict, contraband and war. It falls almost at the bottom of the list of the most corrupt and poorly governed countries, including the Corruption Perceptions Index produced by Transparency International.

Estimates from local watchdog Integrity Watch Afghanistan show bribe payments — for everything from enrolling in elementary school to getting a permit — doubled between 2007 and 2009, topping $1 billion a year. Corruption and black-market trading, which is closely linked to drugs and arms trafficking, have reached over $12 billion annually, according to calculations by NATO.

Yet the Afghan government is reportedly going to the meeting without a clear plan of attack against corruption. There is a strategy — known as the National Priority Program on Transparency and Accountability — but it has not been fully endorsed by the government or international representatives. A large part of the critique is that it is not realistic or ambitious enough.

In the past, many mistakes have been made in addressing corruption, including turning a blind eye. Corruption has been used as a “currency for peace” and is interwoven with the Afghan political economy. Shifting the tide on corruption will have to start from the top down — on the part of the Afghan government and donor countries — as well as the bottom up from local communities.

At the top, there already have been some positive moves. There is now a joint Afghan-donor government body on anti-corruption. It combines a highly reputed group of Afghan and international experts, including a former French judge, Eva Joly, who work to monitor anti-corruption progress against clear goals and benchmarks.

Still greater political will and stronger leadership are needed in order to take action against those accused of state looting. This includes members of the government and their families.

One key step forward would be the adoption of an access to information law, which has yet to pass. Greater levels of transparency and accountability are essential across the board. This is particularly true as Afghanistan begins to develop its estimated $3 trillion in mineral, oil and gas reserves.

Donors also have to do their own share of work at the top. In recent years, key donors have provided technical and financial support for anti-corruption programs. But their efforts have not always been appropriate in the Afghan context, sufficiently coordinated, or integrated with other reforms.

At times, donors have also been criticized for pushing too much funding out too quickly because of internal “spending pressures.” They have also been guilty of a lack of transparency about their aid and military spending.

It’s time for both the Afghan government and donors to renew their commitment to fighting corruption and set up concrete milestones to mark progress. They need to develop an anti-corruption capacity at both central and local government levels. This can include investing in local civil-society organizations that can perform watchdog functions.

All this is predicated on a will for greater transparency.

The question is whether the local context allows citizens to actually speak up against corruption, be protected from reprisals and see their complaints turned into clear government responses at the local and national level. Another question is whether these interventions are eliminating the worst forms of corruption, such as bribery among the police and in commerce.

It would be naïve to imagine that corruption can be halted in Afghanistan through these measures alone. Since the first pledges of aid were made in Berlin in 2004, hard lessons have been learned and the reality that corruption is undoing the rebuilding efforts cannot be ignored, particularly in light of the expected donor drawdown after 2014.

The Tokyo meeting offers a unique chance to commit to real progress in the corruption fight. Let’s hope that the governments don’t let this chance slip by.

Huguette Labelle is chairwoman of Transparency International, an anti-corruption organization.

Characters Count: 5620