The New York Times, December 12, 2010

Jailed Afghan Drug Lord Was Informer on U.S. Payroll

At the height of his power, Mr. Juma Khan was secretly flown to Washington for a series of clandestine meetings with C.I.A. and D.E.A. officials in 2006

By James Risen

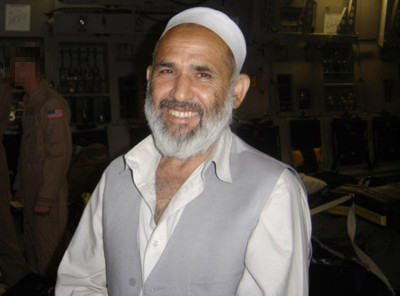

WASHINGTON — When Hajji Juma Khan was arrested and transported to New York to face charges under a new American narco-terrorism law in 2008, federal prosecutors described him as perhaps the biggest and most dangerous drug lord in Afghanistan, a shadowy figure who had helped keep the Taliban in business with a steady stream of money and weapons.

New York Times, December 12, 2010: Hajji Juma Khan, a drug lord, had been on US payroll. At the height of his power, Mr. Juma Khan was secretly flown to Washington for a series of clandestine meetings with C.I.A. and D.E.A. officials in 2006. Even then, the United States was receiving reports that he was on his way to becoming Afghanistan’s most important narcotics trafficker by taking over the drug operations of his rivals and paying off Taliban leaders and corrupt politicians in President Hamid Karzai’s government. (Photo: http://islam.vim.im/juma-khan)

But what the government did not say was that Mr. Juma Khan was also a longtime American informer, who provided information about the Taliban, Afghan corruption and other drug traffickers. Central Intelligence Agency officers and Drug Enforcement Administration agents relied on him as a valued source for years, even as he was building one of Afghanistan’s biggest drug operations after the United States-led invasion of the country, according to current and former American officials. Along the way, he was also paid a large amount of cash by the United States.

At the height of his power, Mr. Juma Khan was secretly flown to Washington for a series of clandestine meetings with C.I.A. and D.E.A. officials in 2006. Even then, the United States was receiving reports that he was on his way to becoming Afghanistan’s most important narcotics trafficker by taking over the drug operations of his rivals and paying off Taliban leaders and corrupt politicians in President Hamid Karzai’s government.

In a series of videotaped meetings in Washington hotels, Mr. Juma Khan offered tantalizing leads to the C.I.A. and D.E.A., in return for what he hoped would be protected status as an American asset, according to American officials. And then, before he left the United States, he took a side trip to New York to see the sights and do some shopping, according to two people briefed on the case.

The relationship between the United States government and Mr. Juma Khan is another illustration of how the war on drugs and the war on terrorism have sometimes collided, particularly in Afghanistan, where drug dealing, the insurgency and the government often overlap.

To be sure, American intelligence has worked closely with figures other than Mr. Juma Khan suspected of drug trade ties, including Ahmed Wali Karzai, the president’s half brother, and Hajji Bashir Noorzai, who was arrested in 2005. Mr. Karzai has denied being involved in the drug trade.

A Shifting Policy

Afghan drug lords have often been useful sources of information about the Taliban. But relying on them has also put the United States in the position of looking the other way as these informers ply their trade in a country that by many accounts has become a narco-state.

The case of Mr. Juma Khan also shows how counternarcotics policy has repeatedly shifted during the nine-year American occupation of Afghanistan, getting caught between the conflicting priorities of counterterrorism and nation building, so much so that Mr. Juma Khan was never sure which way to jump, according to officials who spoke on the condition that they not be identified.

When asked about Mr. Juma Khan’s relationship with the C.I.A., a spokesman for the spy agency said that the “C.I.A. does not, as a rule, comment on matters pending before U.S. courts.” A D.E.A. spokesman also declined to comment on his agency’s relationship with Mr. Juma Khan.

His New York lawyer, Steven Zissou, denied that Mr. Juma Khan had ever supported the Taliban or worked for the C.I.A.

“There have been many things said about Hajji Juma Khan,” Mr. Zissou said, “and most of what has been said, including that he worked for the C.I.A., is false. What is true is that H. J. K. has never been an enemy of the United States and has never supported the Taliban or any other group that threatens Americans.”

A spokeswoman for the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, which is handling Mr. Juma Khan’s prosecution, declined to comment.

However, defending the relationship, one American official said, “You’re not going to get intelligence in a war zone from Ward Cleaver or Florence Nightingale.”

At first, Mr. Juma Khan, an illiterate trafficker in his mid-50s from Afghanistan’s remote Nimroz Province, in the border region where southwestern Afghanistan meets both Iran and Pakistan, was a big winner from the American-led invasion. He had been a provincial drug smuggler in southwestern Afghanistan in the 1990s, when the Taliban governed the country. But it was not until after the Taliban’s ouster that he rose to national prominence, taking advantage of a record surge in opium production in Afghanistan after the invasion.

Briefly detained by American forces after the 2001 fall of the Taliban, he was quickly released, even though American officials knew at the time that he was involved in narcotics trafficking, according to several current and former American officials. During the first few years of its occupation of Afghanistan, the United States was focused entirely on capturing or killing leaders of Al Qaeda, and it ignored drug trafficking, because American military commanders believed that policing drugs got in the way of their core counterterrorism mission.

Opium and heroin production soared, and the narcotics trade came to account for nearly half of the Afghan economy.

Concerns, but No Action

By 2004, Mr. Juma Khan had gained control over routes from southern Afghanistan to Pakistan’s Makran Coast, where heroin is loaded onto freighters for the trip to the Middle East, as well as overland routes through western Afghanistan to Iran and Turkey. To keep his routes open and the drugs flowing, he lavished bribes on all the warring factions, from the Taliban to the Pakistani intelligence service to the Karzai government, according to current and former American officials.

The scale of his drug organization grew to stunning levels, according to the federal indictment against him. It was in both the wholesale and the retail drug businesses, providing raw materials for other drug organizations while also processing finished drugs on its own.

Bush administration officials first began to talk about him publicly in 2004, when Robert B. Charles, then the assistant secretary of state for international narcotics and law enforcement, told Time magazine that Mr. Juma Khan was a drug lord “obviously very tightly tied to the Taliban.”

Such high-level concern did not lead to any action against Mr. Juma Khan. But Mr. Noorzai, one of his rivals, was lured to New York and arrested in 2005, which allowed Mr. Juma Khan to expand his empire.

In a 2006 confidential report to the drug agency reviewed by The New York Times, an Afghan informer stated that Mr. Juma Khan was working with Ahmed Wali Karzai, the political boss of southern Afghanistan, to take control of the drug trafficking operations left behind by Mr. Noorzai. Some current and former American counternarcotics officials say they believe that Mr. Karzai provided security and protection for Mr. Juma Khan’s operations.

Mr. Karzai denied any involvement with the drug trade and said that he had never met Mr. Juma Khan. “I have never even seen his face,” he said through a spokesman. He denied having any business or security arrangement with him. “Ask them for proof instead of lies,” he added.

Mr. Juma Khan’s reported efforts to take over from Mr. Noorzai came just as he went to Washington to meet with the C.I.A. and the drug agency, former American officials say. By then, Mr. Juma Khan had been working as an informer for both agencies for several years, officials said. He had met repeatedly with C.I.A. officers in Afghanistan beginning in 2001 or 2002, and had also developed a relationship with the drug agency’s country attaché in Kabul, former American officials say.

He had been paid large amounts of cash by the United States, according to people with knowledge of the case. Along with other tribal leaders in his region, he was given a share of as much as $2 million in payments to help oppose the Taliban. The payments are said to have been made by either the C.I.A. or the United States military.

The 2006 Washington meetings were an opportunity for both sides to determine, in face-to-face talks, whether they could take their relationship to a new level of even longer-term cooperation.

“I think this was an opportunity to drill down and see what he would be able to provide,” one former American official said. “I think it was kind of like saying, ‘O.K., what have you got?’ ”

Business, Not Ideology

While the C.I.A. wanted information about the Taliban, the drug agency had its own agenda for the Washington meetings — information about other Afghan traffickers Mr. Juma Khan worked with, as well as contacts on the supply lines through Turkey and Europe.

One reason the Americans could justify bringing Mr. Juma Khan to Washington was that they claimed to have no solid evidence that he was smuggling drugs into the United States, and there were no criminal charges pending against him in this country.

It is not clear how much intelligence Mr. Juma Khan provided on other drug traffickers or on the Taliban leadership. But the relationship between the C.I.A. and the D.E.A. and Mr. Juma Khan continued for some time after the Washington sessions, officials say.

In fact, when the drug agency contacted him again in October 2008 to invite him to another meeting, he went willingly, believing that the Americans wanted to continue the discussions they had with him in Washington. He even paid his own way to Jakarta, Indonesia, to meet with the agency, current and former officials said.

But this time, instead of enjoying fancy hotels and friendly talks, Mr. Juma Khan was arrested and flown to New York, and this time he was not allowed to go shopping.

It is unclear why the government decided to go after Mr. Juma Khan. Some officials suggest that he never came through with breakthrough intelligence. Others say that he became so big that he was hard to ignore, and that the United States shifted its priorities to make pursuing drug dealers a higher priority.

The Justice Department has used a 2006 narco-terrorism law against Mr. Juma Khan, one that makes it easier for American prosecutors to go after foreign drug traffickers who are not smuggling directly into the United States if the government can show they have ties to terrorist organizations.

The federal indictment shows that the drug agency eventually got a cooperating informer who could provide evidence that Mr. Juma Khan was making payoffs to the Taliban to keep his drug operation going, something intelligence operatives had known for years.

The federal indictment against Mr. Juma Khan said the payments were “in exchange for protection for the organization’s drug trafficking operations.” The alleged payoffs were what linked him to the Taliban and permitted the government to make its case.

But even some current and former American counternarcotics officials are skeptical of the government’s claims that Mr. Juma Khan was a strong supporter of the Taliban.

“He was not ideological,” one former official said. “He made payments to them. He made payments to government officials. It was part of the business.”

Now, plea negotiations are quietly under way. A plea bargain might keep many of the details of his relationship to the United States out of the public record.

Characters Count: 13578